Growing Resources for Climate Justice Grassroots

Taking A Look Back at NCRP’s Inaugural climate philanthropy report, Cultivating the Grassroots: A Winning Approach for Environment and Climate Funders

As panelists attending the Funders Network conference in New Orleans discussed the resources for funding grassroots climate groups, a familiar message range true. Despite the plentiful local and global case studies of successful local efforts that are mitigating some of the worst impacts of climate change, funding of grassroots solutions remained underfunded and overlooked by mainstream philanthropy. According to Candid, “Most philanthropic climate change mitigation funding stays in the Global North promoting top-down approaches, with only 3.75 percent of funding going toward justice- and equity-oriented efforts.”

Calls from grassroots organizations like the Climate Justice Alliance, and funder networks such as Edge Funders Alliance, the CLIMA Fund, and the Regenerative Economies Organizing Collaborative (REO) echo the alarm that NCRP first sounded in its 2012 report, Cultivating the Grassroots. Principally authored by consultant and former Elias Foundation Program Officer Sarah Hansen, the report outlined the practical and moral need to shift resources to local communities and movements in the climate justice fight.

Hansen wrote that despite the increasing pace of social change around the world, the environment and climate movement was failing to “keep up with movements for justice and equality.” What, if anything, has changed since then?

What We Saw Then

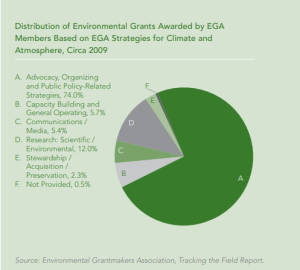

NCRP research noted how in 2009, environmental organizations with budgets of more than $5 million received half of all contributions and grants made to all environmental organizations, despite comprising just 2 percent of environmental public charities.

“From 2007-2009, only 15 percent of environmental grant dollars were classified as benefitting marginalized communities, and only 11 percent were classified as advancing social justice strategies like policy change, advocacy, community organizing, and civic engagement. In the same time period, grant dollars donated by funders who committed more than 25 percent of their total dollars to the environment were three times less likely to be classified as benefitting marginalized groups than the grant dollars given by environmental funders in general.”

Hansen zeroed in on the fact that for all the increasing money invested in top-down approaches and funding of national groups, public policy on the issue had barely moved since the mid-1980s.

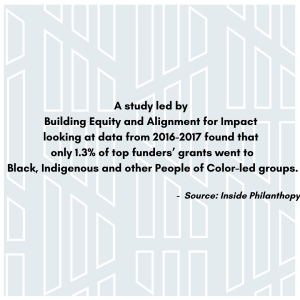

One of the stats cited in NCRP’s 2012 Report, Cultivating the Grassroots: A Winning Approach for Environment and Climate Funders.

“By engaging meaningfully at the grassroots level, grantmakers have the opportunity not just to support efforts that are especially strong but to use their work at the local level to build political pressure and mobilize for national change,” wrote Hansen. “Grassroots organizing is especially powerful where economic, social, political and environmental harms overlap to keep certain communities at the margins.”

The report included examples that evidenced the kind of high- impact, cost-effective grassroots organizing that grantmakers could fund towards a more just future. Case studies included looking at the work of Arizona’s Sky Island Alliance, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s New Constituencies for the Environment” (NCE) initiative and a look into Patagonia, Inc’s Environmental Initiatives with grassroots groups like Louisiana’s Bucket Brigade. It also included specific concrete suggestions for how environment and climate funders can engage with this vast potential constituency.

NCRP Executive Director Aaron Dorfman saw in the data a missed opportunity for the sector—to capitalize on the freedom to innovate which their size and wealth often brings.

“They’ve got the freedom to take risks and experiment,” Dorfman told the Public News Service. “Foundations are supposed to be society’s ‘passing gear,’ to really invest in things that might not attract support otherwise.”

Kathy Sessions, then-Director of the Health and Environmental Funders Network agreed.

“This NCRP report underscores how far communities living amidst environmental health hazards have stretched modest investments to protect their families and the places where they live, work and play,” wrote Sessions. “It provides pragmatic guidance for philanthropy to better equip affected communities to raise awareness, strengthen policy initiatives, and mobilize majority support for stronger environmental protection.”

For Senowa Mize-Fox, NCRP’s Senior Movement Engagement Associate for Climate Justice, this report, which predates her time at the organization, echoed a lot of what she was seeing and hearing anecdotally from movements. “Organizations and communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis have become accustomed to working with less, knowing that steady and sustained funding has never been guaranteed. It does not have to, nor should it be that way.”

WHERE ARE WE TODAY?

So what has happened in the 11 years since CTG was published? It’s a mixed bag.

More of the sector generally sees impacted movements, impacted communities and their leaders as having a more central role in climate solutions. Funders like Larry Kramer of the Hewlett Foundation see the contemporary climate philanthropy that emerged since then as being largely successful. “[I]n 2007, the globe was on track for say 5 to 6 degrees of warming by the end of the century which is civilization ending. We are now, between what has been done and pledged, on track for 2.7 to 3.2 [degrees]” (Climate One 2019, 07:40).

Yet imagine what change COULD have occurred in the last decade if the grassroots and marginalized folks who are at the forefront of the environmental justice movement building had gotten an equitable share of the funding pie? While any dip in the rate of warming is cause for some celebration, the sad reality is that an average of 3 degrees of warming will still be catastrophic, especially to traditionally marginalized groups. Until environmental justice resources scale up grassroots solutions and fully support local leadership, we know that the costs of the climate crisis will keep being borne mostly by those who have the least amount of wealth, economic mobility and opportunities.

Just as worrisome, as an Edge Funders report points out, is that “mainstream climate philanthropy is inextricably linked to the green capitalist approach that currently dominates the international climate conversation…. As emissions continue to surge and extreme weather events grow in intensity and frequency, vulnerable groups remain disproportionately affected.” Even though potentially billions of funding was set aside for grassroots groups and environmental justice priorities as part of last year’s Inflation Reduction Act federal legislation, groups like the Climate Justice Alliance point out that these government efforts, mirroring philanthropic trends, do more to support the fossil fuel industry than climate justice solutions.

WHAT STILL RINGS TRUE TODAY

No matter how you look at the past, the truth is that way too many local organizations today are being underfunded and ignored across a number of sectors. According to a report issued by Inside Philanthropy, a study led by Building Equity and Alignment for Impact looking at data from 2016-2017 found that only 1.3% of top funders’ grants went to Black, Indigenous and other People of Color-led groups, and 91% of environmental justice funding went to organizations that did not state EJ as their primary mission. Also, the most recent Enviromental Grantmakers Association (EGA) research found that only 7% of all climate grants from their members went to environmental justice groups.

In their place are a growing number of vanity and ill-conceived projects by billionaires donors who often bring little to no expertise or connections to frontline communities. Their focus tends to be on finding large scale “one-size-fits-all” approaches frequently at odds with or actively harmful to grassroots climate justice efforts. Their wealth and influence often hoist up pet projects and favored approaches, regardless of whether they are effective or appropriate in addressing the lived experience of the diversity of communities facing this crisis on the ground. Mostly what billionaire climate influencers are chasing is a solution to the problem of environmental injustice that promises profits for investors.

Locally driven, community-based efforts hold critical lessons and successful examples of how to have a tangible and sustainable impact on the worst effects of the climate crisis. Yet the narrative assumption is that the expertise of tech businessmen like Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates at profiting off an exploitive capitalist market will translate into climate solutions that benefit those most impacted by those exploitive systems more than the wallets of a select few.

Coalitions like CJA, the Donor of Colors Network, Edge Funders and REO are encouraging philanthropy to resist that, calling once again for a shift in the way the sector approaches funding decisions around climate. As Edge Funders recently wrote:

“A radically different approach to climate action is urgently needed, and this means radically rethinking philanthropy’s role in the climate debate. One that breaks with predominant framings and with the “one-size-fits-all” strategy that still dominates the climate philanthropy space (and the climate policy space more broadly). One that builds on the lessons learnt during the last 15 years of philanthropic engagement.”

One that started with reports like NCRP’s Cultivating the Grassroots.

Additional reporting and research provided by Jennifer Amuzie, Senowa Mize-Fox, Spencer Ozer, Stephanie Peng and Ryan Schlegel.