As the South Grows

Learn MoreINTRODUCTORY LETTER

Learn MoreEXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Learn MoreINTRODUCTION

Learn MoreTHE BOTTOM LINE

Learn MoreGETTING STARTED

Learn MoreOn Fertile Soil

Updated 4/11/17 to correct spelling of Fannie Lou Hamer’s name.

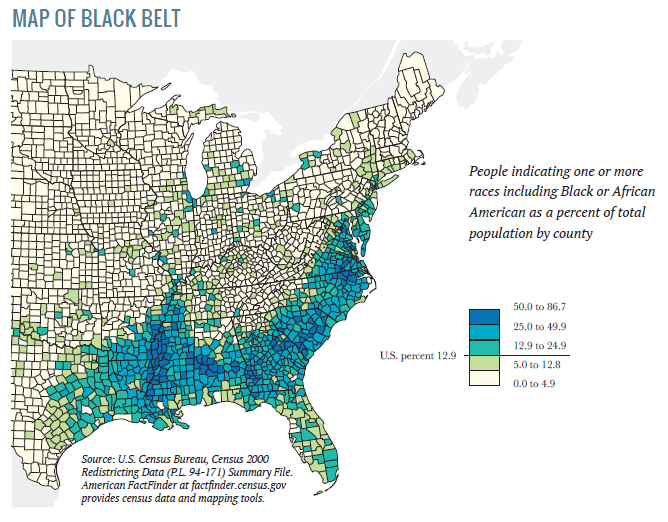

The Black Belt is a swath of fertile soil – and an eponymous region – that extends from Virginia south through the Carolinas before arcing west through the Deep South and ending in the Mississippi Delta. Beginning in the 1600s, European colonizers brought enslaved Africans to the Black Belt, where the colonizers devised a system of slave labor supported by a racial supremacy myth and a culture of violence that worked enslaved Black people to death to reap profit from the Black Belt’s land. The “cotton boom” brought fantastic wealth to white slave owners and made the region home to large communities of Black farmers, most enslaved.

The Black Belt is a swath of fertile soil – and an eponymous region – that extends from Virginia south through the Carolinas before arcing west through the Deep South and ending in the Mississippi Delta. Beginning in the 1600s, European colonizers brought enslaved Africans to the Black Belt, where the colonizers devised a system of slave labor supported by a racial supremacy myth and a culture of violence that worked enslaved Black people to death to reap profit from the Black Belt’s land. The “cotton boom” brought fantastic wealth to white slave owners and made the region home to large communities of Black farmers, most enslaved.

In the wake of slavery’s destruction during the Civil War, these Black farmers attempted to reclaim the land in addition to reclaiming their labor. Former masters foiled their efforts to establish a free agricultural economy by passing draconian labor laws, which reinstated slavery in all but name and reestablished white control over the land. In the decades after emancipation, tenant farming in the Deep South replaced slavery as the primary method of extracting wealth from the land and suppressing Black self-determination.i Centuries later, those tenant farmers’ descendants still grow cotton, corn, okra and other crops on small farms across the Deep South.

We spoke with four of those descendants to talk about the ongoing work of building self-determination in the Deep South.

Black Belt Citizens Fighting for Health and Justice President Esther Calhoun speaks during a press conference at a march for independence from environmental racism in Uniontown, Alabama, on July 3, 2015.

Esther Calhoun

Uniontown, Alabama

Health, Environment and Racial Justice Activist

Esther Calhoun lives in Uniontown, Alabama, population 2,400, where for generations her family earned a living through farming. Uniontown residents are mostly poor and mostly Black, and, much like the other small towns that sprout up across the Alabama Black Belt, they are proud of their home.

“I was born and raised in Uniontown,” said Calhoun during our interview.

The drive from Selma to Uniontown crosses 30 miles of rolling farmland and pine forest until – just a few miles before Uniontown – the turnoff for the Arrowhead Landfill appears and so does the reason why Calhoun was the target of a $30 million libel and slander lawsuit.

That’s because Uniontown is also now home to 4 million cubic yards of toxic coal ash, dumped there in 2010 after an environmental disaster in Tennessee led the Tennessee Valley Authority and their partner company – Green Group LLC – to ship it south to Calhoun’s backyard. Since then, Calhoun and the organization she leads, Black Belt Citizens Fighting for Health and Justice (BBCFHJ), have been vocal about the public health consequences of the dump. And they’ve been asking pointed questions about the implications of moving the waste from a predominantly white, middle-class community in Tennessee to Uniontown.

“We took pictures [of] the waters coming off the landfill. We had a scientist test the waters that had arsenic in it. We had the EPA come from Georgia to view how close this huge mountain [of landfill] is. Alabama Department of Environmental Management allows sewage water to flow into the creek. The creek flows down, and it goes from community to community,” said Calhoun, describing the basics of the environmental and public health threats posed by the waste. “There is sewage that’s contaminating the water, and children are drinking this water.”

In 2016, Green Group sued Calhoun and the BBCFHJ, alleging that the activist and her organization have knowingly misrepresented the facts of living with the toxic waste dump and impugned the company.

Largely because of the lack of power in Black, Hispanic and poor communities in the Deep South, politicians have made it easier for low-wage, environmentally destructive industry to take root in the region. In 2016, the Alabama Black Belt had a poverty rate of 27.7 percent – higher than the national rate of 15.5 percent and the Alabama statewide rate of 19.2 percent. In many Mississippi Delta counties, the poverty rate exceeds 30 percent, and in some it reaches 40 percent.

Esther and BBCFHJ persist despite the lawsuit and intimidating strength of their opposition. The organization – which is sponsored by regional community organizing and leadership development powerhouse Project South – has built a coalition of Alabamians across race, class and gender lines. They have garnered the attention of national environmental groups, and Calhoun has drawn comparisons to another daughter of the Deep South: civil rights activist and philanthropist Fannie Lou Hamer.

Like Hamer, Esther does not have a college education. She and BBCFHJ do not have the resources to file for 501(c)3 status or to develop an advanced fundraising plan. Calhoun and her organization have struggled to get the resources they need because, despite their demonstrated capacity and their work’s radical intersectionality, they have not yet attracted the investments of foundations or other donors.

“You know living in the Alabama Black Belt we don’t get any attention; that’s the problem. We the ones that need the funds because we down here on the ground. We’re the ones that are suffering,” said Calhoun. “I mean there’s so much going on in these little towns, and we don’t have the funding and a lot of people is overlooked. We’re going to get affected with all the environmental injustice. I mean I’ve been to different places, but Uniontown is so overburdened; I’ve never been in a place like this that is so overburdened with so much environmental injustice and environmental racism.”

Calhoun described some of the needs and challenges she has encountered in her efforts to save her home town.

“We don’t even know which way to turn,” said Calhoun. “People around here need help, and when we reach out for help we get overlooked. We need lawyers, we need water testing. I mean I could go on and on and on. We’re dealing with the landfill going out trespassing on our Black cemetery. And I know it’s happening in other areas, too, but we don’t have the funding to confirm it. And it is so, so overwhelming because in big cities they get money and whatever they need but rural areas don’t get the attention they need and we’re the ones that are funded last.”

And there’s the underlying racism that’s prevalent in some of her dealings with those who purport to help. “Some of these environmental people – just because we’re in a rural area and Black, they look at us funny. If you’re Black, they don’t really want to deal with you,” shared Calhoun. “They’ll say little things, but they don’t really want to help the Blacks, you know what I’m saying? They act like it, ’cause they want to hear your story and they want to put their name on it. Well, we was out there helping Black Belt citizens, but what do they do?”

Marginalized people across the South often do not have the power to determine the destinies of their communities. But the Deep South is fertile ground for more than cotton. Beginning in the 1950s, the network of Black civic and religious leaders across the region was the foundation on which Dr. King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Congress of Racial Equity, Student of Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other organizations built the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March. Later that year, as a result of national attention drawn to Selma and the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act – and the fight for the beloved community continued.

As the nation turned away from legalized racial discrimination, its prison system expanded, disproportionately locking up people of color. The Sentencing Project estimates that in Alabama between 1980 and 2014, the state’s incarcerated population more than quadrupled while its total population grew by 25 percent.ii

Across the South – and the country – the penal system grew like a weed, taking the place of mental health care facilities and crowding out other kinds of infrastructure investments in rural communities.iii Black Southerners began to fill prisons and were once again stripped of their voting rights in the process.

Pastor Kenneth Glasgow

Pastor Kenneth Glasgow

Dothan, Alabama

Criminal Justice Reform Activist

From his home in Dothan, at the southeast corner of Alabama just 16 miles north of the Florida line, Pastor Kenneth Glasgow is organizing a nationwide movement of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people to demand civil rights, humane treatment and a second chance at a happy, healthy life.

“My ultimate goal has always been to gain an equilibrium across the board and in doing so, I have to look at the justice system and recognize the disparity,” said Glasgow. “The racial disparity behind bars, in the bails and even in the whole set up of the courtroom setting in the South.”

In the fall of 2016, Glasgow was the spokesperson for one of the biggest prison strikes in American history. He spent hours on his phone – bouncing between calls with reporters from The New York Times and Buzzfeed News to text messages from strike leaders inside prisons across Alabama, the South and, eventually, the country.

Pastor Glasgow understands what has been apparent to many for decades: Mass incarceration disproportionately deprives people of color of economic, political and physical self-determination in a way that can be traced straight back to slavery. Glasgow leads The Ordinary People Society (TOPS), a faith-based 501(c)3 organization working to empower those most affected by mass incarceration. Unlike many criminal justice-focused organizations, TOPS has representation inside and outside the penal system.

But until recently, TOPS’s work has attracted little philanthropic support. The Southern Partners Fund, a small public foundation in Atlanta, and the Drug Policy Alliance in Washington, D.C., have provided lifeline support. Glasgow works in deep relationship with Project South. The high-risk venture philanthropists at Open Philanthropy Project have recently made significant investments in TOPS’s work. But, for all the national acclaim TOPS’s successes have garnered, most foundations have declined to invest.

“No one thinks that anything can ever get done in the South,” said Glasgow. “It took until a couple of years ago when I started changing all these laws and then people started looking and saying, ‘Wait a minute. How could you say nothing could get done in Alabama and this guy just changed the laws in Alabama and got bipartisan efforts going to have the things reformed? How can you say nothing can happen now in Alabama when Glasgow won a lawsuit in 2008 causing people inside Alabama prisons to be able to vote?’”iv

Glasgow also spoke about the challenges of getting philanthropic support.

“Funders and foundations set up criteria that will not fit grassroots organizations so what they end up getting is a person that looks good on paper but actually isn’t doing any work,” said Glasgow. “They know the language, they have the grammatical skills, they write this awesome proposal, and they’ve never even been inside a prison, never even been on the street. Are [foundations] basing it on whether the person has a company, basing it on what they do, basing on the work they are committed to and have done or are you just basing it on somebody that can fit your criteria on paper?”

He offered advice to grantmakers and donors about how to pick grantees and what kind of capacity they need to look out for to make an impact on criminal justice reform in the South.

“If you really want something to attach your foundation money to that is going to get you whatever goal you want to reach, you’ll want to attach it to one of the grassroots organizations that’s actually on the ground doing the work that’s dealing with the directly impacted people, not somebody in an ivory tower with a beautiful office and a full staff on payroll but they ain’t getting no work done,” Glasgow shared. “In the South, you can lobby all the hell you want to, but our resource here is not money because we don’t have none. Our resource here is relationships.”

He urged funders to look for organizations that are walking the talk.

“You got a whole bunch of criminal justice organizations out here that say ‘we’re fighting for these people that are locked up, that are formally incarcerated,’” he cautioned. “Check out all the organizations that do stuff for criminal justice and are fighting for people incarcerated, formerly incarcerated and see how many of them hired somebody that is not directly impacted, formerly incarcerated. … [Ask them] How many [formerly incarcerated people] do you got on your board? How many of them have you hired?”

Glasgow saw firsthand the importance of involving the very people he sought to serve in what he, his organization and partners have accomplished.

“The system changes started in 2009 when we created the formerly incarcerated and convicted people’s movement. We got together and brainstormed, came up with formerly convicted people movement – we got about 40 different delegates,” he recounted. “We now have what’s called the Super 8. For the past four years, we’ve been going back and forth with the Department of Justice, on monthly phone calls, even quarterly physical meetings in Washington at the Department of Justice.”

Pastor Glasgow, TOPS, their connections at Project South and the Southern Movement Assembly and his network of incarcerated community organizers have changed Alabama policy to restore the franchise to thousands of Alabamians; they have organized a nationwide prison strike, and now they influence federal policy decisions on race and criminal justice.

Grantees aren’t the only ones with valuable perspective on power-building work in the Deep South. We spoke to Southern funders, too, and they helped us better understand the balancing act that foundations – especially smaller foundations – are called to perform.

Ivye Allen

Ivye Allen

Jackson, Mississippi

Foundation Executive

Ivye Allen’s decades of work in Southern philanthropy have made her a pragmatist. She leads the Foundation for the Mid South in Jackson, six hours west of Dothan on meandering Highway 84. The foundation represents a certain kind of grantee-centered, Black-led philanthropy that is sparse but powerful across the South.

Integral to the foundation’s work is a strategic emphasis on public-private partnerships to improve the lives of people living across the Midsouth region. Those partnerships can be challenging in the South’s political environment, but Ivye and the foundation understand that, without partners who cross the ideological spectrum and come to the table with different skills, resources and priorities, addressing entrenched poverty and racially disparate educational outcomes will be next to impossible.

Allen will be first to tell you that the South’s most valuable asset is its leaders. “One of the key assets is individual and community leaders who have been there and who are there. Those people will put in their heart and soul to move their communities forward,” she said.

And she acknowledged the challenge racism presents for those leaders without downplaying their ability to affect change.

“Oftentimes our partners tend to be Caucasian. In some of the smaller Delta towns you have mayors of color, but if you’re working on a county level, or wherever there’s resources, there’s still some Caucasians that are in control of that pot of money,” noted Allen. “So, recognizing that and never losing sight of why we’re at the table, if I can get the other folks to bring their resources, then the more the better.”

She’s also aware of the challenge of talking about race. “Employers are not thinking of having more black welders, they just need welders. It’s about knowing when to push your agenda,” said Allen. “[It’s] always having your agenda top of mind, but knowing when to use certain language, and when to let it slide but do what you need to do.”

Allen also addressed the misperception among foundations about the lack of capacity in the South.

“People think of the South and think there’s no capacity there. Not true. People have the skill sets; some of them, more than we know, have book knowledge. But they also have a lot of experience, even if they don’t have the technical aspect of it,” explained Allen. “Those leaders are going to continue to be there, whether we are in there investing or not. So how do you help people who don’t look at you as just a handout but look at you as a partner in helping to move their respective communities forward?”

“Another asset is really being intentional about having a diversity of voices at the table,” Allen added. From the county supervisor and mayor to members of the community who are most affected, “It’s the only way the community is going to move forward,” she said.

Having these diverse voices come together comes with its own challenges. Allen shared her experience of a press conference announcing the Re-Entry Council, which is made up of the Department of Corrections, the attorney general, judges and the foundation.

“We had put together a press conference to announce the effort, and in the press release, I said this is a wonderful thing, ‘and a disproportionate number of people in the criminal justice system are males of color,’” she recalled. “My program person said to me ‘Everybody’s backing out of the press conference. They’re all mainly white; they’re not comfortable with us talking about race.’ So I said, ‘take the statement out,’ and he said, ‘really? You’re going to let it go?’ And I said, ‘why do I care, it’s about the work we’ve done.’”

They took the statement out and the announcement was made. “But when one of my board members went up to talk, he didn’t know anything about the negotiation, and he said, ‘There’s just a disproportionate number of black males in the prison system,’” Allen continued. “Behind him was all those people. It took me being willing to let that go in order to talk about the bigger piece of it.”

Allen’s perspective on when and how to pursue an explicit agenda is not shared by every Southern nonprofit leader or activist. Allen herself recognizes the plurality of personal and organizational agendas that converge in work like hers across the region.

“I don’t kid myself – I think the state correctional people were at the table because they would be overwhelmed with having too many people in the system,” she said. “It’s about checking your ego at the door in order to make sure that you’re looking at the long battle of what we’re trying to do. In the South, we do that every day.”

Despite the strong hold conservative politicians have on state governments across the South, Southern nonprofit advocates and community leaders are working to change policies and address the impacts of structural racism and sexism in Southern community life.

Carol Burnett

Carol Burnett

Biloxi, Mississippi

Women’s economic security advocate

Three hours down Highway 49 from Ivye Allen’s office in Jackson, Carol Burnett is in Biloxi at the Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative strategizing ways to make Mississippi women more economically secure.

Burnett – like many nonprofit leaders in the South – wears many hats. She’s an ordained minister, a Center for American Progress Fair and Reproductive Justice Leader and director of another local nonprofit. Her experience as a faith leader, a direct service provider, a state agency director and now statewide advocate is reflected in her deep, nuanced analysis of the ways race and gender intersect to disadvantage Mississippi women.

The Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative was born out of Burnett’s experience as a provider of child care and job training for low-income women. She recognized that many of the challenges her organization faced were policy challenges – policies need to be changed so the women they worked with and for could experience the economic security they deserved.

“You have evidence that shows that investments in [child care] are good from everywhere you look at it, whether you’re looking at it from the perspective of the child or the parent or the employer or the economy,” said Burnett. “And yet there is still complete resistance to investing money in this program.”

By learning from women affected by poverty, sexism and racism and translating that learning into a state-level campaign for increased access to child care, job training and other supportive services, Burnett linked together grassroots direct service and grass-tops advocacy. It’s a link common in the South, where organizations have to get by with little resources.

Burnett, as with Allen and other Southern nonprofit leaders, is pragmatic about the challenges her work is up against and knows that it’s important to read between the lines.

“Much of the work we’re trying to do is to change policy and that means appealing to elected officials or state agency people to do things that they don’t really want to do,” she shared. “Most of the time the reason they don’t want to do them isn’t the reason they articulate. It has more to do with underlying values and prejudices in my opinion.”

The Initiative’s longest battle has been the fight to secure more state money to support child care programs for low-income working mothers. Despite gathering extensive evidence about the tremendous benefits of such policies, like better education outcomes, lower absenteeism and turnover, higher worker productivity and less reliance on public assistance, officials and policymakers in Mississippi continue to strongly resist such programs.

“So you have to ask ‘why is that?’” said Burnett. “The only conclusion that you can draw based on the conversations and the decisions that people make, the opinions they express, is that there is a real mix of attitudes that women should be home taking care of their children and that these poor women of color shouldn’t have had the kid in the first place because they can’t afford it. The program suffers from all those attitudes about race, poverty and gender.”

The MLICCI has a consistent and committed group of funders, but Burnett’s role as a Southern nonprofit leader gives her valuable perspective about the ways the Southern nonprofit ecosystem is often misunderstood by foundations.

“I think there are organizations that have done some really good work that are frequently not recognized. Because they’re not known to outside entities, the assumption is they’re not here or if they are here they don’t really know what they’re doing, and the best thing to do is to bring somebody national here to introduce a resource because there couldn’t possibly be one here,” shared Burnett. “That has happened so many times I can’t tell you. It’s not only insulting, but it fails to work because of the attitude toward outsiders. People come here with assumptions that there is not already a floor of resources or a floor of infrastructure, and by the time they’ve learned that, their grant is up and they’re gone.”

She also shared one valuable tip for foundations: Gender is key.

“My advice to foundations is to add an analysis of gender to their toolbox to understand the problems facing the South,” said Burnett. “And find ways to support cross-issue organizing in this environment where all our issues, and I think our entire democracy, are at stake.”

Photo by Jloranger, used under Creative Commons license.

i. Nancy O’Brien Wagner, “Slavery by Another Name,” Bluestem Heritage Group, 2012, https://bento.cdn.pbs.org/hostedbento-prod/filer_public/SBAN/Images/Classrooms/Slavery%20by%20Another%20Name%20History%20Background_Final.pdf.

ii. The Sentencing Project, “State by State Data – Alabama,” http://www.sentencingproject.org/the-facts/#map.

iii. Darrell Steinberg, David Mills, and Michael Romano, “When did prisons become acceptablemental healthcare facilities?” Stanford Law School, February 19, 2015, http://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/child-page/632655/doc/slspublic/Report_v12.pdf; Ryan S. King, Marc Mauer, and Tracy Huling, “Big Prisons, Small Towns: Prison Economics in Rural America,” The Sentencing Project¸ February 2003, http://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Big-Prisons-Small-Towns-Prison-Economics-in-Rural-America.pdf.

iv. Ebony Davis, “Former Alabama prison inmates could have voting rights restored before general election,” Dothan Eagle, June 29, 2016, http://www.dothaneagle.com/news/local/former-alabama-prison-inmates-could-have-voting-rights-restored-before/article_fffb85f6-3e34-11e6-bb76-234c516c4dc6.html; AL.com, “Alabama ex-convict helps former prison inmates regain voting rights,” October 30, 2016, http://www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2016/10/alabama_ex-convict_helping_for.html.

As the South Grows

Learn MoreINTRODUCTORY LETTER

Learn MoreEXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Learn MoreINTRODUCTION

Learn MoreTHE BOTTOM LINE

Learn MoreGETTING STARTED

Learn MoreAdvisory Committee and Black Belt + Delta Interview and Focus Group Participants

READ MORE